“In terms of knowledge culture, software embeds ideologies, historical biases, and epistemologies of efficiency or control. Hardware, in turn, carries its own logics, constraints, and affordances, and is shaped by place-based knowledge and embodied expertise. As such, software is not just code, and hardware is not just material object. Together, they are living epistemic materials, shaping how we know, build, and dwell in the world. As agentive materials, they actively shape the landscape and the city.”

- e flux; Technoecologies

“We don’t speak about free speech when the algorithm is hidden”

- Emmanuel Macron

The AI system is the largest global infrastructure system we have ever been in the process of building. And it is happening without any government oversight, built into areas already in economic and social neglect.

The spatial configuration of present-day AI infrastructure increasingly distributes computing power away from users, relocating it in privatized, highly polluting super centers such as xAI’s Colossus:

A former Electrolux facility was transformed into the xAI data centre by local architect firm Gresham Smith Photo: Gresham Smith (via eflux)

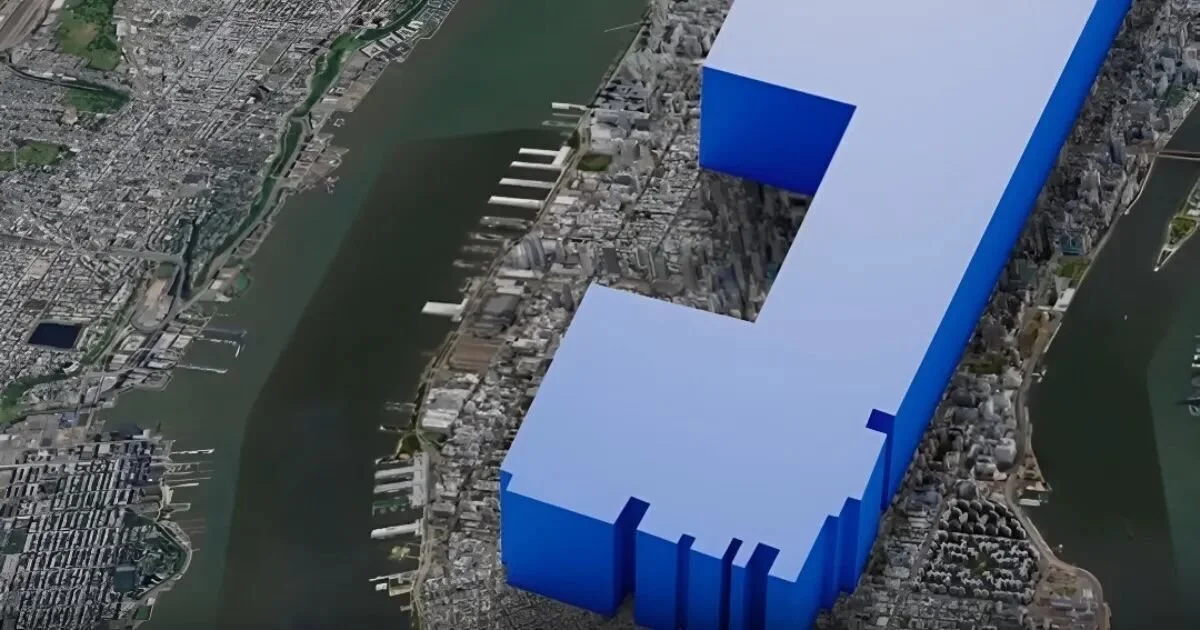

Recently the Meta CEO (Zuckerberg) shared an image meant to convey the scale of Hyperion, the new data centre by Meta under construction in Louisiana:

Hyperion data centre size in relation to Manhattan. The accuracy of this image is debatable but the opacity speaks for itself. Image: Meta

OpenAI is also in progress of building 5 new data centres in Texas. “Stargate” has a planned capacity to nearly 7 gigawatts, roughly the same amount of power as seven large-scale nuclear reactors.

Construction underway on a Project Stargate AI infrastructure site in Abilene, Texas, in April 2025. Photo: Daniel Cole /Reuters

AI is not immaterial, it is becoming more and more material without us really noticing it. How do we deal with it?

This text is focusing on the impact that data centres has, will have, and could potentially have, through a sustainability, infrastructural and social-technical lens. It aims to show how they (the data centres) are fundamentally entangled with sustainability pathways. Situating their development within sustainable development and interacting with (but not limited to) the following SDG goals:

SDG #7: affordable and clean energy

SDG #9: industry, innovation and infrastructure

SDG #12: responsible consumption and production

SDG #13: climate action through mitigation and adaptation

The data centres are often built in areas of water scarcity and we know they are resource demanding. However, when has that stopped humanity going forward with an invention that benefits the elite? An article published in the Financial Times the 29th of November 2025 quoted OpenAI in “building AI infrastructure is the single most important thing we can do to meet surging global demand…the current compute shortage is the single biggest constraint on OpenAI’s ability to grow”. To combat this they are doing what Trump want them to do; “build baby, build”. They are doing so through investment funds, without taking on any financial risk themselves. How do we prepare for a society where the AI sector could require the majority of our produced energy? It highlights the tension between AI development and sustainable development pathways.

How do we think about policy for this? Saying that we should reduce demand by just reducing our individual use of AI is not enough, this requires a collective action.

In The EU act has made an attempt to put in place a policy addressing the models (the transparency of the data), but it does not address the environmental question. It comes down to local government, however the planning authority that grant the construction of these centres is not up to date to be able to address the problematics. Neither, I am sorry to say, is the architecture industry. Everyone is operating in a vacuum and most data centre push back has come from local communities self organising.

“We can no longer afford to think and work in silos” - Ban Ki-Moon UNGA 2015

From an architect and planning perspective, the collective action comes from a more regulated building code. Kate Crawford mentions in an interview with Ramanan Raghavendran in the In Our Hands podcast (issued 14/8 2025) that the current blueprint for the AI infrastructure roll out favours speed over smarts. They are building quick, to the detriment of energy and resource efficiency. But as the roll out of data centres are underway it is shown how the planning regulations need to step up as the top down approach of political policy regulation fails to be realised. If we are accepting the very real reality that Open AI, Microsoft, Google, etc won’t stop wanting to use computational power, then we, as a player in the construction sector, need to explore efficiencies in the infrastructure (on top of political regulations, as we won’t have a silver bullet to this issue). A Jevons paradox situation, where the efficiency gains only leads to increased demand, and thus negating the overall savings, could perhaps be avoided through the requirements put in place at planning approval. By demanding that a data centre won’t outstrip local resources but be built in a closed loop system, the efficacy of the data centre (it s capacity of operation so to speak) would be capped. This is really where we need to update our planning regulations to better deal with the present development.

It is proposed in the article, “The making of critical data center studies”, published on ResearchGate by D. Edwards et al (DOI: 10.1177/13548565231224157) that this new interdisciplinary area of study should be introduced to critically focus on contemporary computing infrastructures. Drawing on concepts and methods from fields including anthropology, history, and science and technology studies, and ranges from studies of the physical infrastructure, real estate and land use aspects of data centres and other AI infrastructures. Architecture and other design disciplines might hold clues to open up spatial and environmental dimensions of this phenomenon.

To spell it out in simple terms. The problem is that we build on the wrong places and we don’t do integrated solutions. It is lazy and good governance should be about preventing this laziness and its inherent pollution and resource waste.

Tri-gen plants, like the CopenHill power plant in Copenhagen by BIG, shows the idea of trying to make “hedonistic sustainability” out of something problematic (meaning that in the field of architecture let new technologies to be harnessed to create unprecedented programs that benefit both the environment and our access to nature in an urbanized world ).

In this waste-to-energy plant positioned within the urban area of Copenhagen, the plants also provides district heating to 160 000 households and a ski slope on its roof.

“Hedonistic Sustainability” project by BIG. Image: https://stateofgreen.com/en/solutions/copenhill/

In a tri-gen system the waste heat is used for district water or space heating and data centres are recognised as places of benefit to be used as a tri-gen system (ecomena.org). It only works, however, when sufficient need exist in relative immediate geographic vicinity.

Would I write a manifesto for AI infrastructure, it would be:

Build only in proximity to urban areas

Be a closed system operating as a tri-gen plant, simultaneously providing free heating/cooling for the urban dwellers.

The entanglement of energy systems and AI infrastructures development are intrinsically linked and we need to push for smarter integrated solutions as we are now starting to build completely new typologies. There is the obligation to check the developments against the “Earth Alignment Criteria (Sustainable consumption and production + Power and access + Social cohesion and trust) and hold privately developed infrastructure accountable.

Narrative to consider

“Immateriality” - only through images of what data centre actually looks like can we start to realise these are not immaterial “clouds” but actual built structures in our environment. How we place them and how we build them is key.

“Put simply: each small moment of convenience – be it answering a question, turning on a light, or playing a song – requires a vast planetary network, fuelled by the extraction of non-renewable materials, labor, and data”

- https://anatomyof.ai/

In architecture the use of AI has, until now, been considered mainly an issue around personal work flow and not becoming obsolete as the AI “toolbox” is introduced. It s been immaterial cloud based tools and digital programs, with us users removed from the material and environmental dimensions of computing, contributing to the obfuscation of its costs and hazards. Hidden is the lifecycle of technological products that depends on the extraction of resources, the environmental mess of industrial process and the designated obsolesce of technological things with a future incarnation as trash.

But the sector needs to be part of the discussion where it can make a difference; providing efficiencies, qualities and regulations around the square meters built on ground.

By focusing on the data centers I don’t want to detract from the other issues that we are facing with AI, such as reinforcing bias and patterns of inequality, and the issues around extraction of raw materials. The situation we are in with exponentially fast expansion of AI infrastructures (with energy and water use only one aspect) requires multidisciplinary action and a an “all hands on deck” approach. For the AI development is fuelled by dreams of modernity and quantum leaps (by a narrow elite), and the results we are seeing is exploding labour, and environmental costs around the world (in particular the Global South. Data centres are becoming strategic assets, but one that comes with a heavy environmental cost.

Exploring alternative ways of ambient cooling by placing the data centres in cooler climates, with renewable energy production and a stable political climate should mean the Nordic/ Scandinavian countries are high on the list for housing data centres.

In architectural discourse it is commonly noted that you cannot just build for a single purpose. Everything you do has to be able to be “this, and…” .

With data centres, location, design and functionality matters. Planning permission is generally about reducing negative impact and about protecting the amenities of the neighbourhood but with the speed of development going on the political initiatives are too slow to form and to trickle down to planning authorities. For these reasons we have architecture and planning boards. They need to step up as they are the last roadblock before the shovel hits the ground. The locations of data centres are critical when it comes to upholding obligations. Marginalised communities are very rarely represented in a meaningful way and it is paramount that the planning and architecture industries engage critically with AI infrastructure as part of spatial justice.

The ambition of this text is to argue the idea of the data centre as tri-gen plant (or similar other integrated energy solution). To become something more than just the data centre.

The opportunities would lie in the data centre supporting district heating/cooling (as discussed in Applied Thermal Engineering) and utilisation of the smart grid to balance peaks with renewable resources. The

Subjugating the data centre design to look at becoming a tri-gen plant would be a challenge, and a cost. But it is a cost the tech industry is capable of wearing.