Image: Kakhovka dam, originally built by the Soviets, blown up by the Soviets, rebuilt by the Ukrainians, blown up by the Russians…

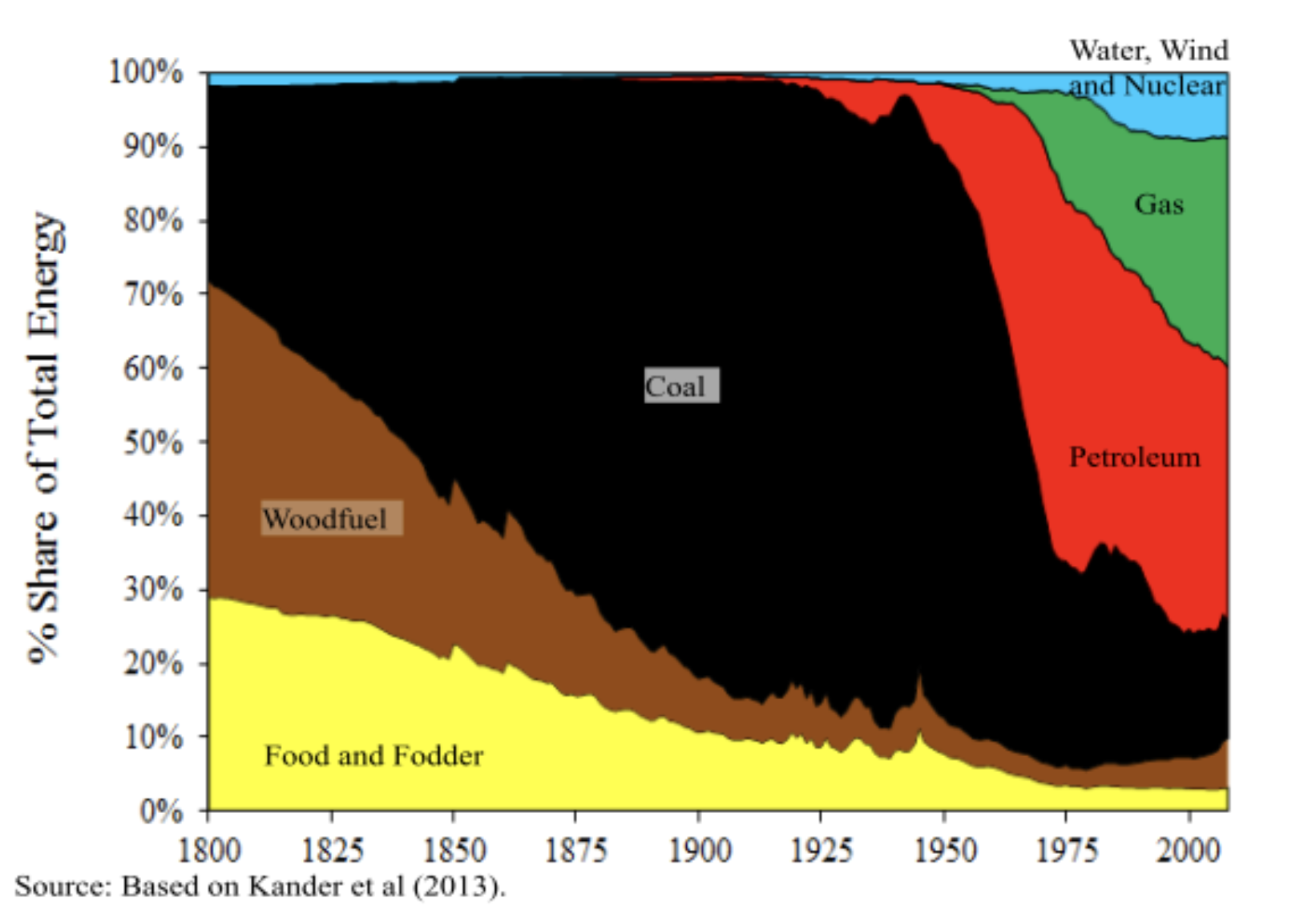

Image. Primary Energy Consumption in Europe (Fouquet 2016)

Image: Comparison of the per capita energy mix in Germany 1990 versus 2024 (Retrieved from Our World in Data)

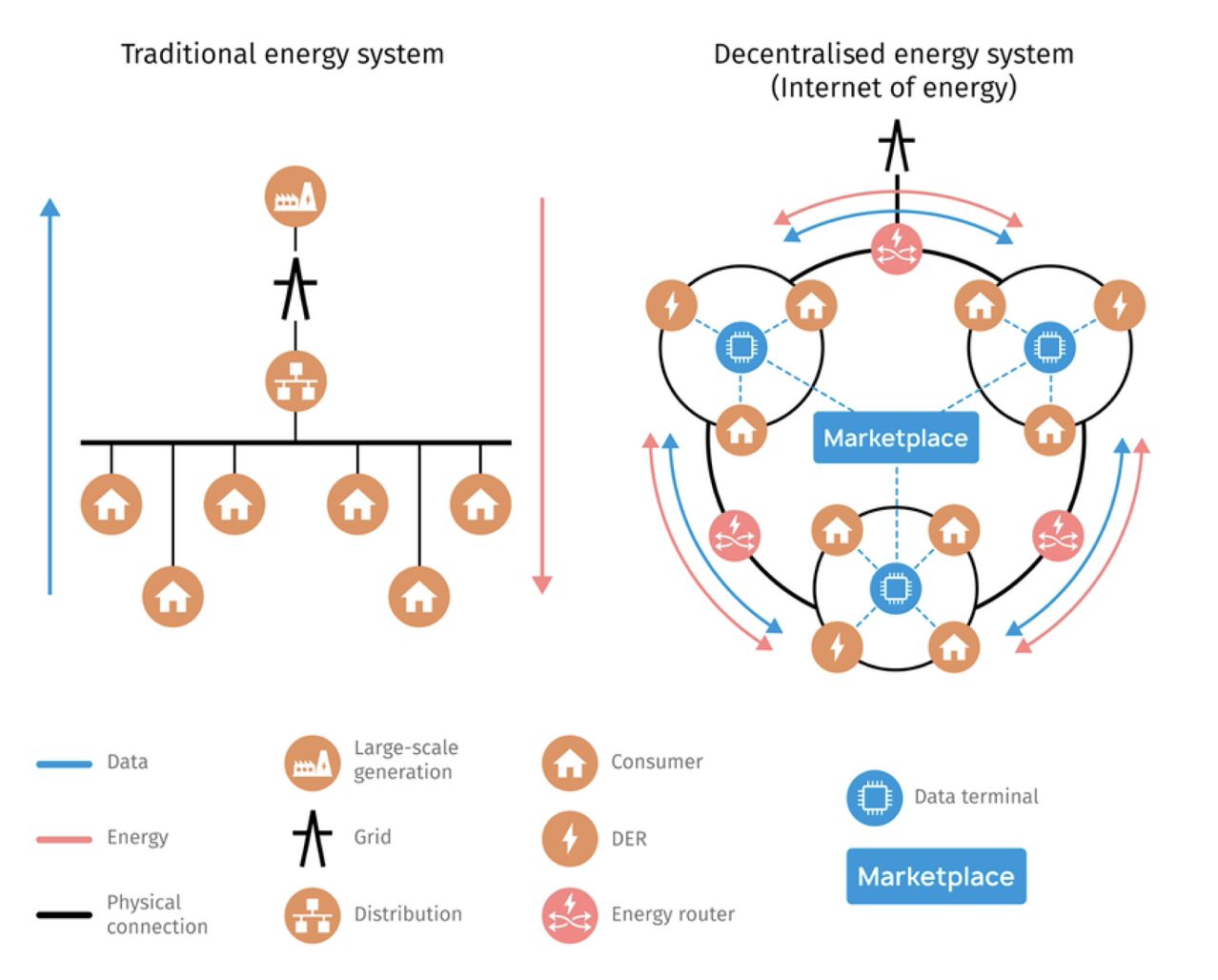

Image . Comparison of the principles of arrangement of centralised and decentralised energy systems (Internet of distributed energy architecture. Version 2.0 - from ResearchGate)

This text explores how energy and geopolitics have shaped patterns of infrastructure design and spatial development in Europe by focusing on Germanys solar transition.

It argues that energy systems not only reflect technological and economic priorities but also express political and cultural power over space and aim to demonstrate that sustainability and resilience of energy systems depend on how and where infrastructure is designed and integrated into the landscape. Germanys solar development is examined as a case where decentralised design reshapes energy geography and public perception.

Energy systems are geopolitical architectures.

Every major shift in civilisation stems from how societies capture and organise energy, a process that defines not only productivity but also spatial order and the design and placement of energy infrastructure thus hold both material and political significance (Smil 2017).

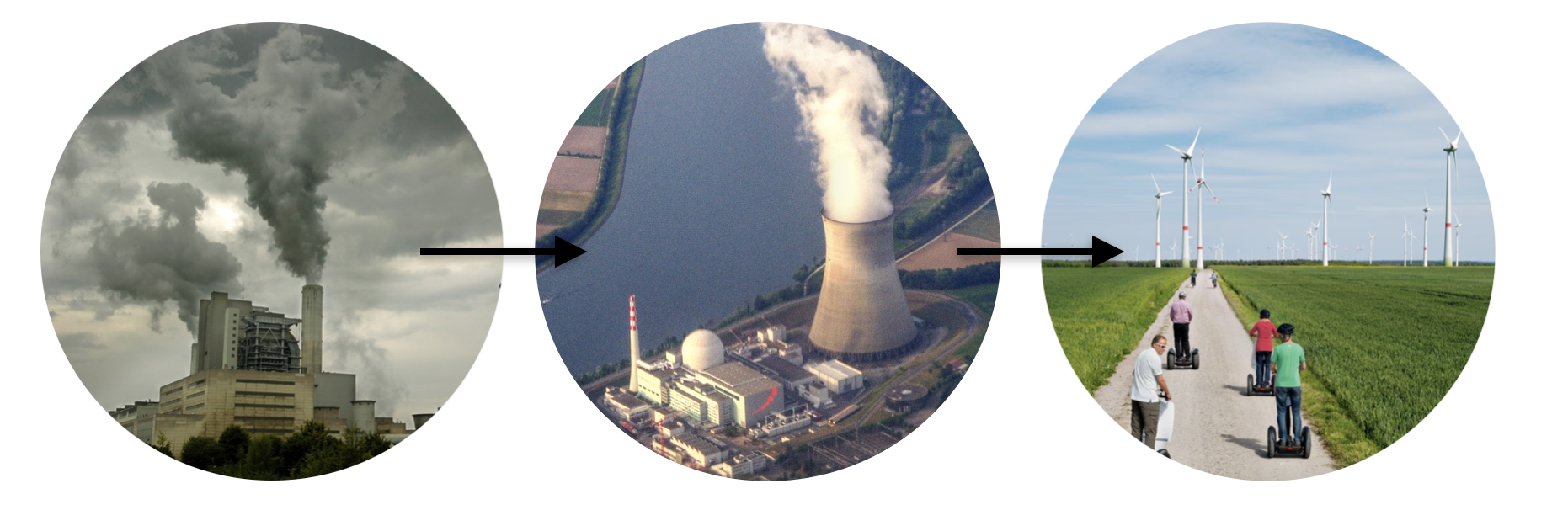

Energy and geopolitics have long determined the form and location of Europe’s infrastructure. In Germany coal-fired industrial cities dominated the start of the 20th century, following with nuclear as intermediate and now investing heavily in renewables. How do these changes manifest differently in the landscape and in public perception, both with regards to supply, production and distribution. How can an energy technology be delivered in such a way to contribute to a systems overall resilience in a period of geopolitical instability.

Image: Frimmersdorf in Germany, Europe's second dirtiest power plant (WWF Germany), Isar Nuclear plan in Bavaria (Google images), German wind power field (Google images)

Coal defined early modern Europe by concentrating power in regions like Germany’s Ruhr Valley, where dense networks of extraction, industry, and settlement emerged. Energy availability determined national strength and the spatial concentration of urban life.

Germany invested in infrastructure, R&D and channelling citizen capacity in different coal processing technologies, and due to its position as Europes largest industrial economy, Germany set technological and infrastructure norms across much of the continent. It entrenched geopolitical dependencies and hindered the development of alternative energy technologies.

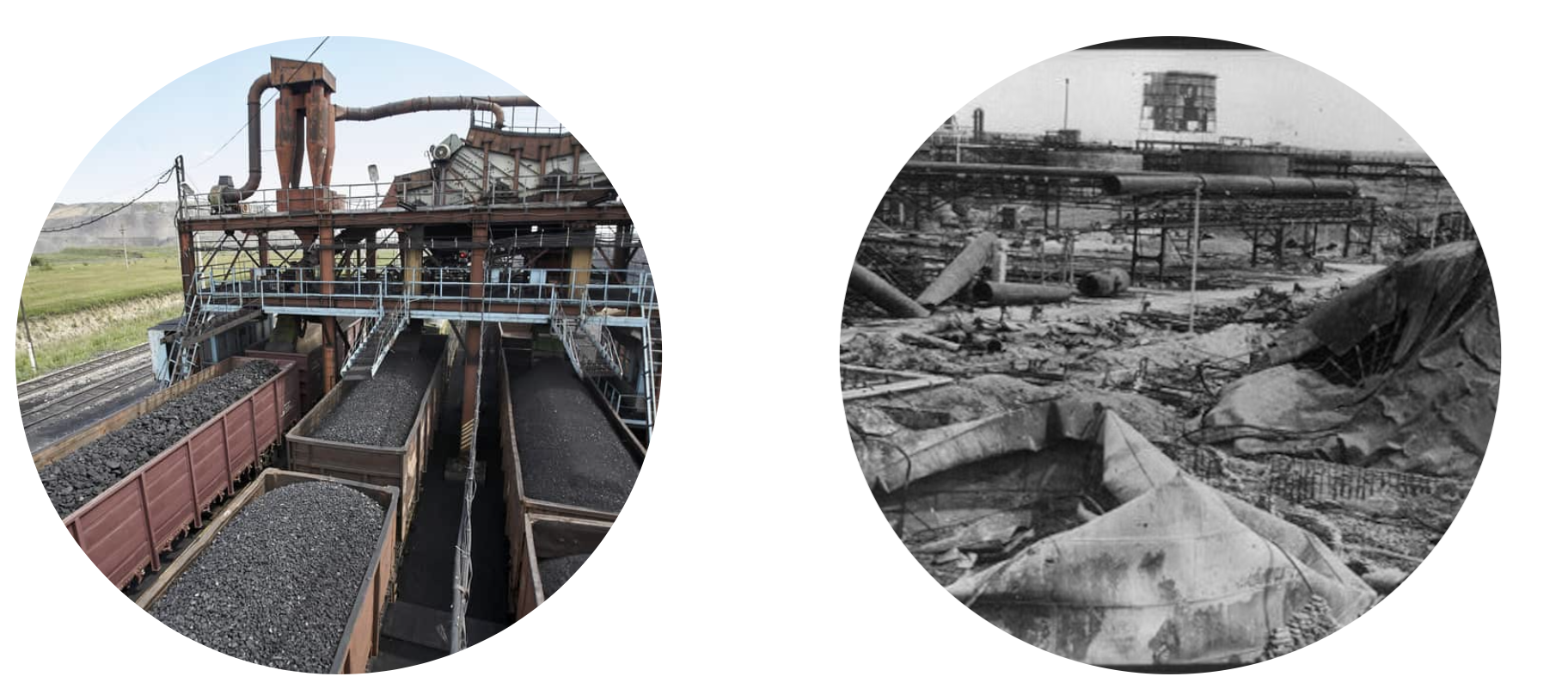

Image: Coal loaded on train (Google image), German infrastructure bombed by Allies in WWII (Google image)

The reliance on a small number of large scale, complex and energy-intensive facilities to provide energy and fuel makes you highly vulnerable, as proved during the course of WWII and allied bombings. The energy produced by coal saw a rapid decline and by the middle of the century Germany was in need of diversifying its energy supply.

A major player to go into this was Siemens, a long standing German company that had been heavily involved with the Nazi war effort and that, after the war, was forced to reorganise and rebuild itself after experiencing heavy damage.

Never waste a crisis.

In the 1970s, under the name Kraftwerk, it becomes one of Europe’s largest nuclear engineering firms, this during the time nuclear movement saw rapid expansion. A top down process imposing itself in the landscape. Large-scale projects were placed according to political and economic convenience, often ignoring their spatial and social impact.

This is when the grassroots green movement is establishing itself, placing nuclear energy (together with coal) as a symbol of state-technocratic power (and threat of nuclear war). The small suppliers of solar and wind became, to a degree, representational of citizen democracy. It was the polar opposite to the centralised coal-nuclear technologies; small-scaled, decentralised and safe.

Image . From “centralised” to “decentralised and modular” energy solutions (United Energy Ventures 2018)

At the back of the Chernobyl accident, an event that preempted the Soviet dissolution, and further aiding the renewable energy development, was the reunification of Germany. To integrate the East and West grids Germany was required to revise how the grid operated, with large energy providers in both East and West being disrupted and allowing renewables a foothold.

Never waste a crisis.

Energy shapes space- we build for how we want to live

The German solar program illustrates how spatial design and legitimacy intersect. Instead of central power stations, generation was distributed across rooftops, fields, and community cooperatives. Solar panels started to be integrated into agricultural landscapes (agrivoltaics) and such strategies align infrastructure with place, creating visible, participatory, and aesthetically coherent systems that invite public support (Ekelund 2010).

Image. Solar panels on roofs and on farmlands (IBC Solar)

A diversified system is in turn more resilient against systemic collapse. Systems can operate independently from the main grid, providing a continuous energy supply even during disruptions. The efficiency should also, in theory, be higher as the power is generated near the end-user, reducing transmission losses.

Image . Comparison of the principles of arrangement of centralised and decentralised energy systems (Internet of distributed energy architecture. Version 2.0 - from ResearchGate)

Persisting challenges

Renewable systems, while cleaner, are material-intensive and spatially diffuse. Their large land footprint has come with a new set of grassroots objections, aka NIMBY-isms, and dependence on global supply chains create new vulnerabilities around who controls the sources. Sustainability depends on designing infrastructures that are not only accepted but also resilient within their environments across the whole production line.

Energy infrastructure transitions happens through external pressure (actual or implied) and thus Germany’s solar shift can be read as an environmental and strategic re-territorialization, redistributing power literally and politically.

Decentralized renewables reduce vulnerability to external actors and it strengthens local energy autonomy, however to achieve long term success depends on spatial legitimacy, meaning the fit between an energy system, its physical setting, and public perception. The design and placement of energy infrastructure thus hold both material and political significance.

The future of energy resilience in Europe lies not only in new technologies but in the deliberate design of place - how they are experienced on ground. Where and how we build determines not only how energy flows, but how societies align around it; technically, politically and culturally.

Written on behalf of KTH “Energy and Geopolitics”